The British Indian army grew from 200,000 at wars start to roughly 2.5Million. They fought everywhere- from India to Africa to Europe, though in Europe they only fought in Italy. Around 85,000 Indian troops died in the war mostly fighting Japan. However, including wounded and captured, roughly 150,000 were lost. Compared to it’s numbers, India lost very few soldiers. However, it also fought in some of the worst theaters and proved itself a competent fighting force.At the outbreak of war, the British-Indian army was somewhere around 2.5 million strong.

The numbers are staggering: up to three million Bengalis were killed by famine, more than half a million South Asian refugees fled Myanmar (formerly Burma), 2.3 million soldiers manned the Indian army and 89,000 of them died in military service.

South Asia was transformed dramatically during the war years as India became a vast garrison and supply-ground for the war against the Japanese in South-East Asia.

Yet, this part of the British Empire's history is only just emerging. By looking beyond the statistics to the stories of individual lives the Indian role in the war becomes truly meaningful.

Has the massive South Asian contribution to the World War Two been overlooked?

In some ways, it hasn't.

Everyone has heard of the Gurkhas and many people have heard something of the role of Indian soldiers at major battles like Tobruk, Monte Cassino, Kohima and Imphal.

The Fourteenth Army, a multinational force of British, Indian and African units turned the tide in Asia by recapturing Burma for the Allies. Thirty Indians won Victoria Crosses in the 1940s.

Untold stories

Increasingly, for both the World War One and Two, the contribution of soldiers from across the Empire-Commonwealth has been coming to light.

But what about all the other people who were caught up in the war?

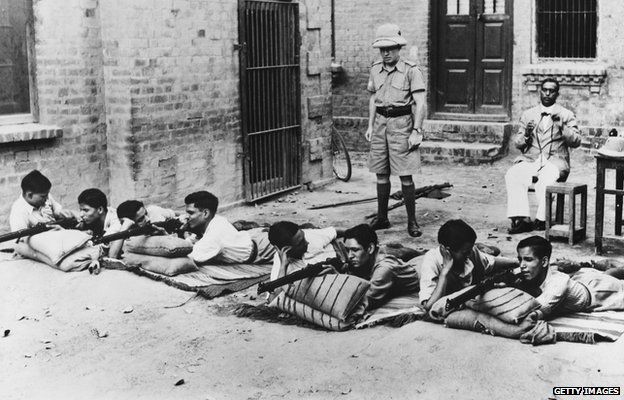

Numerous other South Asian people sweated behind the scenes to secure supply lines and to support the Allies.

There were non-combatants like cooks, tailors, mechanics and washermen, such as a boot-maker to the Indian army named simply as Ghafur who died at the battle of Keren in present-day Eritrea and whose grave can still be seen there today.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

What do we know about the thousands of women who mined coal for wartime in Bihar and central India, working right up until childbirth? Or the gangs of plantation labourers from southern India who travelled up into the mountains of the northeast to hack out roads towards Myanmar and China? Or the lascars (merchant seamen) such as Mubarak Ali, remembered simply as "a baker" who died in the Atlantic when the SS City of Benares was torpedoed?

There were millions of other South Asians working towards the imperial war effort and we never hear about them.

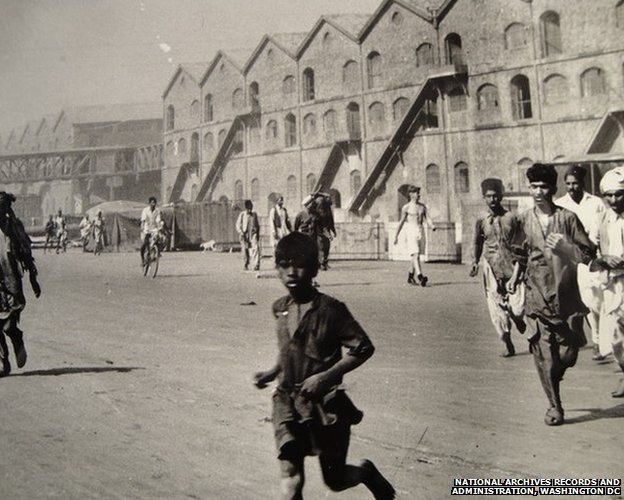

It wasn't glamorous work: "coolies" loading and unloading cargo at imperial ports or clearing land for aerodromes did not share the prestige of fighter-pilots.

But their work could be very dangerous.

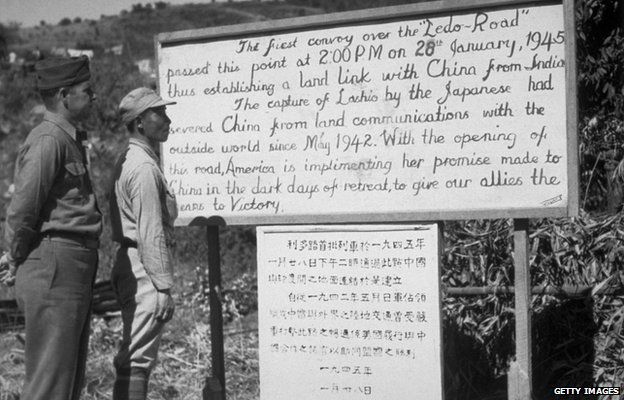

Thousands of Asian labourers died building treacherous roads at high altitude, including the Ledo Road between China and India, working with basic pickaxes and falling prey to malaria and other tropical diseases.

Harbour accident

Others died in industrial accidents - there was an incredible explosion in Bombay harbour in 1944, when a ship loaded with explosives and cotton caught alight, blew warships to smithereens and made over 80,000 homeless.

Factory workers and dockworkers also suffered from aerial bombardment - official figures suggest several thousand deaths from Japanese bombs on India's eastern coastline.

The men and women who kept the imperial war effort going in South Asia did not write diaries and memoirs.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Often for them it was just a job, a way of earning enough money to eat.

They did not see it as belonging to a heroic part of world history, worthy of inclusion in history books. The illiterate left little trace of their service. And often their work - hard and poorly paid - was tough and dangerous whether it was wartime or not.

British officers wrote hundreds of accounts of their time in South Asia but there is not a single written memoir by an Indian rock-breaker, road builder or miner.

Quick profits

It's not a simple story of heroism or patriotism; many of these workers were more motivated by the need for bread than by the need to defeat the Axis.

And it's not a straightforward case of imperial exploitation - many elite South Asians made quick profits in the war and transformed their own fortunes.

Experiences of the 1940s depended on caste, class, vantage point and region: a Punjabi soldier could see things very differently to a metropolitan student in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) or a factory-owner in Kolkata (Calcutta).

OTHER

OTHER GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Often those who worked towards the war were Anglo-Indians, adivasis [tribespeople], Parsis and Christians - and their histories slipped by the wayside during the writing of post-independence nationalist myths.

The people who made up the war effort soon had their lives shaped again by the Partition of 1947 and the carving up of new countries.

This wartime history belongs to Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan as much as to India.

In the rush to write new histories of nation states after 1947, much of the history of the 1940s was locked out from official memory. Tales of the freedom struggle took precedence. And in Britain and the US, the emphasis was placed on remembering military contributions to major battles, not on the everyday lives of anonymous workers.

As one report put it at the time, this was not the "forgotten army", but the "unknown army". Perhaps now we can finally start to appreciate the fullest extent of WW2.

They fought and died wherever the empire was , fighting in Asia against the Japanese, in Africa against the Italians and on mainland Europe against the Germans.

Due to the independence movement, 40,000 captured Indian soldiers actually fought with the Japanese against the Allies, primarily British dominion forces.

With out Indian support, world war II would have been a different war entirely.

The plains around the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey are infused with memories of the Great War. This was the site for the bloody Battle of Gallipoli, or the Dardanelles Campaign, between the Ottoman Empire and the Allied forces that took place between Feb 17, 1915, and Jan 9, 1916. During my visit to the Gallipoli Battle Museum a couple of months ago, I came across an interesting facet of the conflict: it was the first psychological warfare campaign. “The planes of the Ottoman forces dropped propaganda sheets in Urdu for the Muslim soldiers of British India,” said a caption under one of the photographs there.

Why are we in the subcontinent oblivious to the participation of some 1.4 million voiceless Indian soldiers who were serving the British Empire during the Great War? Around the world these days one comes across commemorative ceremonies for the first industrialised war that shook the world a hundred years ago. It was known as the ‘war to end all wars’, though this is far from true. And though the distressing realities of the war and its trenches have materialised across debates and books, what remains scarcely remembered is the contribution of British-Indian (present-day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Myanmar) soldiers, of which some 73,000 were sent to their graves.

As waves of nationalism and anti-colonialism surged in the Indian subcontinent in the early 20th century, enthusiasm emerged for an independent India. Promises were made by the Empire to grant India independence after the Great War was over. Princely states swore loyalty and pledged their resources to the imperialists while the main political parties, including the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League, agreed to support the war effort, says Professor Santanu Das from Kings College, London. The Indian sepoys [sipahis] were then deployed across the Western Front to retaliate against the ‘enemy’ forces of their colonial rulers, in Mesopotamia, Gallipoli, North and East Africa.

Bullets, gas, and bombs decimated the sepoys but there are hardly any written accounts of these Indian troops who are now recognised as the largest voluntary army in the world. World War I history is heavily comprised of various forms of literature and journals, and the illiteracy factor amongst these soldiers doesn’t allow for much understanding of their experience. “Most of the soldiers were non-literate and hence did not leave behind the abundance of memoirs, poems and journals that form the cornerstone of World War I memory,” says Prof Das.

The Indian troop divisions had their own diversifying factors as well. There were ethnic groups such as the Pathans, Jats, Garwahalis and Gurkhas; the men straddled the Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh faith. They fought far from their homelands, unprepared, and against an enemy they did not know. Many were peasants and put their lives on the line to feed their families.

Mulk Raj Anand’s fictional Across the Black Waters presents the delirium of the Indian soldier while serving in the war. Anand, through his protagonist Lalu — an Indian sipahi under British rule — unflinchingly paints the confusion and naïveté that bind the soldier and his understanding of war.

The sipahis’ participation subjected them to marginalisation, given the British ideology of white supremacy. According to Prof Das, there were pockets of warmth and friendship between the Indian sepoys and their British officers, but the overall power-hierarchies and racism remained intact: the junior-most British officer was usually senior to the senior-most Indian soldier.

Ironically, one of the main reasons these soldiers are hardly remembered by the communities to which they belonged is because they were serving their oppressors. If the British had been more principled and had granted India self-rule after the Great War as they had promised, these troops would have been heroes.

The whispers of these forgotten soldiers susurrate in a collection edited by Davis Omissi, Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldiers’ Letters, 1914-18. In Omissi’s work, one comes across the coded echo of an Indian bugler from Kitchener’s Indian Hospital in 1915, reflecting the censorship that was prevalent to maintain the morale of the Indian army: “The black pepper is finished now. Now, the red pepper is being used, but occasionally the black pepper proves useful” — code for European and Indian troops.

Still, the fragmented accounts of these soldiers do not reflect the intensity of their experience. But weaving these in with prisoners-of-war recordings, photographs, and paintings could present some coherent picture of South Asians’ experience of the Great War. Prof Das, in his upcoming book India, Empire and First World War Culture: Literature, Images, Songs, aims to portray this. “We need to go beyond the battle-names and Victoria Crosses of military history and recover the human stories at the heart of the war,” he insists. “It’s not limited to the battles of Neuve Chapelle or Cambrai but diffused in a much wider sphere of culture, from Gandhi giving recruitment speeches to sepoys’ letters, poems and songs, to Muhammad Iqbal and Rabindranath Tagore writing about the war.”

In place of the first jihad camp in Germany, where Muslims were recruited from different parts of the world to fight in World War I, there is now a refugee camp. Located in the south of Berlin at Wünsdorf-Zossen, it is also where the first mosque in Germany was constructed in 1915.

Speaking at a talk titled ‘Digging deep, Crossing Far’ held at T2F, radio producer Julia Tieke and curator Elke Falat spoke about working on their audio project that documented the role ‘colonial recruits’ from South Asia and the ‘Maghreb’ played in World War I.

Tieke spoke about how she came across a postcard showing the mosque at Wünsdorf-Zossen that first piqued her interest in the project. “Thousands of such postcards were printed to show that Muslims were treated well,” she said. “The Germans had designed a ‘jihad programme’ with the Ottoman Empire. For the Sikhs and Hindus there were small sites as well but the focus was on Muslims.”

She also showed clippings of ‘Hindustani Urdu’ newspaper that was distributed at the camp containing a fatwa from the Ottoman sultan supporting it as well. Most of the ‘colonial’ soldiers at the camp were Prisoners of War who were fighting on behalf of the British and were captured in France.

During their research in Karachi they uncovered an Urdu pamphlet dating back to 1918 asking people to contribute monetarily to the war. Another document shown at the talk was by the Karachi War League in 1917 offering a prize of Rs1,000 for the “best forecast of the war”.

“Although most of the soldiers were recruited from Punjab but they would go through the harbour in Karachi,” said Tieke. She showed an old map of Pakistan showing Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Gilgit Baltistan, Punjab with marking dots and numbers scribbled on it. Those were the locations from where the Prisoners of War at the camp were from along with the number of recruits.

“The jihad programme wasn’t very successful,” added Tieke, “So they stopped quite early and opened the camp to researchers. A person who wanted to record and create an audio museum came and started a commission and would record from these camps.” She showed a photo of men waiting in line to get recorded.

“This was known as the Half Moon camp,” she said adding, “because it had the most faraway and most diverse languages.”

Tags:

National